Chronobiology: The Dynamic Field of Rhythm and Clock Genes

Article Courtesy of The Institute of Functional Medicine

Chronobiology & Circadian Medicine

Chronobiology is the study of biologic rhythms, including circadian rhythms, that follow a daily or ~24-hour cycle. Sleeping at night and being awake during the day is an example of a circadian rhythm related to light. In this instance, the daily light and dark cycle is an important zeitgeber, or natural time cue that influences the circadian pattern.1 Our internal biological clocks produce circadian rhythms that are regulated through clock genes and are involved in the essential functioning of both central and peripheral tissues.1,2 Specifically, to modulate various body processes, core clock genes known as period and cryptochrome genes are believed to act as transcriptional regulators that affect the circadian expression of certain rhythmically expressed genes and proteins.3

Medical chronobiology is a relatively new field that specifically looks at the impact of circadian or other biologic temporal patterns on human diseases;4 the practice of circadian medicine incorporates this knowledge of diurnal biologic rhythms to help inform and potentially improve medical treatment.

A DYNAMIC FIELD

The field of chronobiology is expanding due to its potential to shed light on the influences of timing on human physiology, diseases, and optimal wellness of the individual. Established peer-reviewed journals specific to chronobiology and biological rhythms are associated with annual conferences focused on the latest research and developments in the field.5,6 Of significant note, the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three American researchers for their discoveries of molecular mechanisms that control circadian rhythms.7

At the start of 2020, several review articles were published in peer-reviewed journals synopsizing suggested animal-model and human-based conclusions regarding the detrimental impact that circadian impairment may have on disease states such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease.8-10 Another 2020 review focused on chrononutrition, suggesting that food may be a circadian time cue, or zeitgeber, but suggested that targeted human research is needed for a proper definition.11 Two recent books written by researchers discuss the impact that circadian rhythms may have on a person’s life and offer suggestions on how to harness the power of chronobiology to sleep better, reduce stress, lose weight, and improve health and well-being.12,13

In addition to the expansion in research and media coverage, discoveries in the field of chronobiology are now being translated into clinically applicable interventions known as chronotherapeutics.14 A 2017 review noted that “Erratic eating patterns can disrupt the temporal coordination of metabolism and physiology leading to chronic diseases.”15 The application of chronotherapeutics or chronotherapy would consider an individual patient’s optimal meal timing and address any other temporal disruptions, as well as a patients’ underlying medical condition.14

HEALTH IMPACT FOR THE INDIVIDUAL – CHRONOTYPE

Biological rhythms influence sleep-wake cycles, eating habits and digestion, body temperature, and other biochemical and metabolic processes.1,2 Genetic variations in clock genes, which regulate these rhythms of the body, and environmental factors contribute to potential rhythmic differences between people within a population.16 Chronotype, for example, describes at what time of day a person is naturally inclined to sleep and to be awake, ranging from early types to late types and those in between the two extremes.16

Does the right schedule for a specific chronotype optimize health and well-being? Does the wrong schedule lead to health impairments?

“Social jetlag” is a term used to describe a misalignment between a person’s biological rhythm and the rhythm of their social life, including school, work, and family schedules,16 and it may be associated with increased risk of chronic diseases such as obesity and metabolic disorders.17

The Research: Impacts of Chronobiology on Health and Disease

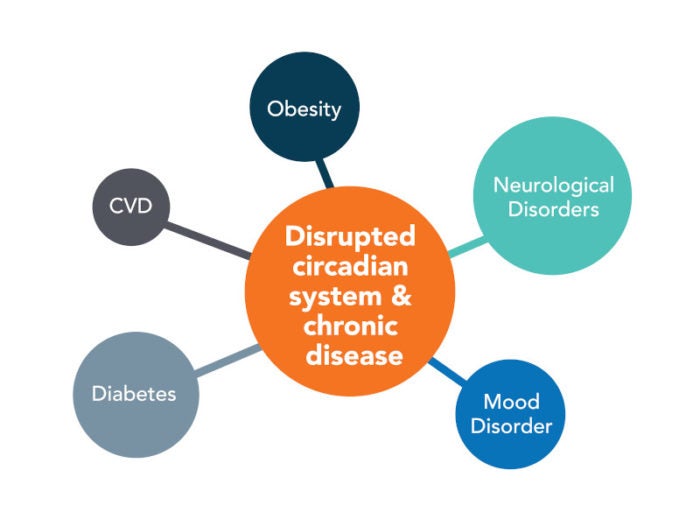

Studies suggest that changes in the circadian-system regulation may be influenced by the aging process.2,18 In addition, circadian-rhythm disruptions have been associated with patterns such as chronic shift work, social jetlag, and meal timing.11,16,17,19 Irregular rhythms have also been linked to sleep disorders, seasonal affective disorder, and various chronic health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, obesity, diabetes, and mood disorders.1,10,20

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Cardiovascular physiology, including heart rate and blood pressure, and the risk of onset of adverse cardiovascular events fluctuate during a 24-hour day.9 Human and animal-based studies suggest circadian rhythms influence cardiovascular function and diseases, and may also offer an avenue for disease prevention and treatment.20-22 In 2019, a study of over 19,000 patients with hypertension found that those who took their medication at bedtime rather than upon awakening had a better ambulatory blood pressure and lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD).22

NEURODEGENERATIVE DISORDERS

Although the etiologies of Parkinson’s disease remain unclear, aging itself is a risk factor, and recent findings suggest that circadian disruptions may influence the progression of the disease.10 Circadian rhythm disturbances may also impact another common neurodegenerative disorder, Alzheimer’s disease (AD).23 While circadian disruption has been reported in symptomatic AD, a 2018 cross-sectional study evaluated data from 189 cognitively normal adults to examine any relationships between circadian functions, aging, and preclinical AD.23 Results from the study indicated fragmentation of the sleep-wake cycle impacted preclinical AD, independent of age, suggesting that presence of irregular circadian rhythm may be an early symptom, or may contribute to early disease development.23

CHRONONUTRITION

The timing of eating has surfaced in several human and animal studies regarding circadian impact on mood disorders, obesity-related chronic diseases, and metabolic disorders.

Mood Disorders

Seasonal affective disorder, typically occurring in autumn and winter months, is a depression related to the changing seasons. Other rhythmic factors such as the timing of meals may also play a role in the development of mood disorders. Results from a 2019 study regarding eating times and mood disorders indicated that of the 1,304 study participants, those who reported skipped or delayed breakfasts were more likely to experience a mood disorder compared to those with a regular schedule of eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner.24

Chronic Disease

A 2020 review noted that glucose metabolism is one of many physiological processes influenced by circadian rhythms, and misalignment of those rhythms may lead to adverse health outcomes.8 In a small study of 28 participants with type 2 diabetes, effects of eating a three-meal diet with a carbohydrate-rich breakfast was compared to a six-meal diet; results after 12 weeks for those following the three-meal diet showed:25

- Increased weight loss.

- Lower fasting, daily, and nocturnal glucose levels.

- An increased expression of clock genes.

The study suggested that the upregulation of the clock genes on a patterned three-meal diet may help to improve glucose metabolism.25

Social Jetlag

Social jetlag may influence meal schedules and prompt food consumption that follows irregular patterns or occurs late at night, conflicting with circadian rhythms and impacting chronic diseases.17 To evaluate the relationship between social jetlag and late-timed meals, researchers conducted a cross-sectional study of 792 participants with obesity-related chronic diseases and found that participants with social jetlag had higher intake of calories, total fat, cholesterol, and sweets and had longer reported eating durations and overall later meal times compared to participants without social jetlag.17 The results suggested that within this tested group, social jetlag was associated with a poorer diet and later meal times, which are not optimal conditions for individuals with obesity-related chronic diseases.17

Shift Work

Studies have suggested that chronic shift work, or employment on a schedule outside of the 9 am to 5 pm work day, increases the risk of CVD,26 and that this increased risk may be influenced by chronically sleeping and eating at irregular circadian times.19 With circadian rhythm disruption emerging as a potential risk factor for obesity and obesity-associated comorbidities such as diabetes and CVD, studies show that patterned diets such as time-restricted feeding (TRF) may reduce this risk.15,21,27 A study using the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster to model obesity suggested that TRF may counteract obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction, even during an irregular lighting schedule meant to mimic shift work conditions.21

CHRONOTHERAPY

Treatment interventions based on circadian rhythms have been seen in light therapy, which is used to alleviate symptoms of seasonal affective disorder and even of non-seasonal depression,7 in patterned dietary habits, which are used to help regulate blood sugar levels,25 and in the optimization of heart disease medications.14,22 A recent review called for a better understanding of circadian impact on neuroinflammation and control of pain to provide new, more effective chronic pain treatments.28

Most recently, researchers have also taken a closer look at maximizing the benefits of exercise by considering diurnal timing.29,30 The picture of optimal exercise times is not entirely clear, and previous clinical studies have had conflicting results regarding impact on circadian rhythms.29,30 However, regarding the extensive network of clock genes in skeletal muscle, specifically, literature has suggested that while rhythm dysregulation of these genes may have harmful metabolic consequences, exercise may reset the circadian clock, alleviating negative effects.29 Further, a 2020 clinical trial investigated a “timed exercise intervention to phase shift the internal circadian rhythm.”30 This small, randomized study focused on sedentary adults and concluded that late chronotypes may have circadian benefit from exercise in the morning or evening while evening exercise may promote circadian misalignment for early chronotypes.30

Research Concerns: Factors to Consider

Circadian medicine has the potential to personalize treatments and improve patient outcomes; however, several concerns have been noted regarding the current research on chronobiology and circadian rhythms:

- In many investigations, the fruit fly and mouse models have been used to mimic human health while testing the impact of circadian timing patterns.21,31-33

- Cellular evidence on the mechanisms of clock genes and circadian control is primarily based on animal models.18,34,35

- Some conclusions have been based on epidemiological studies and observational human studies, with potentially impactful confounding variables.17,21,23

- Not all studies are in agreement. Some studies on topics such as the aging process and altered clock gene expression, the metabolic effects of melatonin or melatonin as a treatment for mood disorders, and phase shifts caused by the timing of exercise have reported conflicting results.7,18,30,36

Overall, the priority for additional human research has surfaced in the literature, especially in regard to the development and implementation of effective chronotherapies. For example, a 2017 review reported on increased evidence that suggests disruptions in sleep and circadian rhythm may worsen symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD);33 however, the evidence was primarily from animal-model research. The authors stated, “There is a clear need for large randomized controlled trials in human patients with IBD where chronotherapeutic strategies can be tested.”33 Even in 2020, a review regarding food as a circadian time cue stated that “Targeted human research should be prioritized to properly ascertain multifaceted relationships between food intake and human chronobiology.”11

Finally, direct consumer genetic testing to determine chronotype is offered through various commercial outlets and is a promising area for future clinical use. However, application of this genetic information toward the optimization of medical treatments and overall improved health has not been well documented in human trials.

Functional Medicine Considerations

The evolving knowledge of medical chronobiology and circadian rhythms provides great potential for furthering the Functional Medicine model’s personalized, root-cause approach to optimal health and wellness. The consideration of an individual’s chronotype may help address underlying causes of chronic conditions, assist in the optimization of personalized treatments, and improve sustainability of lifestyle interventions. Further, while some studies present conflicting results, some suggested potential clinical applications of chronobiology include:

- Light therapy and seasonal depression: Daily light therapy for 20 to 30 minutes is suggested for treatment of several conditions, including seasonal affective disorder, sleep disorders, and even non-seasonal depression.7,37

- Patterned dietary habits for increased clock gene expression and improved glucose metabolism: Glucose metabolism is influenced by circadian rhythms,8 and one study suggested that following a three-meal daily diet lowered glucose levels throughout the day and upregulated circadian genes.25

- Diurnal timing considerations to optimize blood pressure medications: A recent study found that patients who took their blood pressure medication at bedtime rather than upon awakening had improved blood pressure and a lower risk of developing CVD.23

- Chronotype determination to maximize exercise benefits: Exercise may address circadian rhythm misalignment, with one study indicating that “late” chronotypes may show circadian benefit from exercise in the morning or evening.30

Circadian medicine attempts to use knowledge of biological rhythms practically and to maximize therapeutic interventions. Helping patients live in line with their chronotype by exercising, sleeping, or eating at optimal times and on optimal schedules may be essential for the most effective treatment strategy.

Learn more about the latest advancements in Functional Medicine research and the resulting clinical applications at IFM’s 2020 Annual International Conference.

References

- Circadian rhythms. National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Published August 2017. Accessed February 25, 2020. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/pages/factsheet_circadianrhythms.aspx

- Zee PC. Circadian clocks: implication for health and disease. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(4):xiii. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.09.002

- US National Library of Medicine. Genetics home reference: CLOCK gene. Published March 3, 2020. Accessed March 10, 2020. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/CLOCK

- Smolensky MH, D’Alonzo GE. Medical chronobiology: concepts and applications. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147(6 Pt 2):S2-S19. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_2.S2

- International Society for Chronobiology. Home page. Accessed March 3, 2020. http://chronobiology2019.org/

- Society for Research on Biological Rhythms. Schedule of events. Published 2020. Accessed March 3, 2020. https://srbr.org/schedule-of-events/

- Wirz-Justice A. Chronobiology comes of age. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(6):531-533. doi:10.1111/acps.12828

- Mason IC, Qian J, Adler GK, Scheer FAJL. Impact of circadian disruption on glucose metabolism: implications for type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2020;63(3):462-472. doi:10.1007/s00125-019-05059-6

- Rana S, Prabhu SD, Young ME. Chronobiological influence over cardiovascular function: the good, the bad and the ugly. Circ Res. 2020;126(2):258-279. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313349

- Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallée JN. Circadian rhythms, neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the story of Parkinson’s disease. Cells. 2020;9(2):E314. doi:10.3390/cells9020314

- Lewis P, Oster H, Korf HW, Foster RG, Erren TC. Food as a circadian time cue – evidence from human studies. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(4):213-223. doi:10.1038/s41574-020-0318-z

- Panda S. The Circadian Code: Lose Weight, Supercharge Your Energy, and Transform Your Health From Morning to Midnight. Rodale Books; 2018.

- Kshirsagar SG, Seaton MD. Change Your Schedule, Change Your Life: How to Harness the Power of Clock Genes to Lose Weight, Optimize Your Workout, and Finally Get a Good Night’s Sleep. HarperCollins; 2018.

- Tsimakouridze EV, Alibhai FJ, Martino TA. Therapeutic applications of circadian rhythms for the cardiovascular system. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:77. doi:10.3389/fphar.2015.00077

- Manoogian ENC, Panda S. Circadian rhythms, time-restricted feeding, and healthy aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:59-67. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2016.12.006

- Wittmann M, Dinich J, Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(1-2):497-509. doi:10.1080/07420520500545979

- Mota MC, Silva CM, Balieiro LCT, Gonçalves BF, Fahmy WM, Crispim CA. Association between social jetlag food consumption and meal times in patients with obesity-related chronic diseases. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212126

- Duffy JF, Zitting KM, Chinoy ED. Aging and circadian rhythms. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10(4):423-434. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.08.002

- Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(11):4453-4458. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808180106

- Van Laake LW, Lüscher TF, Young ME. The circadian clock in cardiovascular regulation and disease: lessons from the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2017. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(24):2326-2329. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx775

- Villanueva JE, Livelo C, Trujillo AS, et al. Time-restricted feeding restores muscle function in Drosophila models of obesity and circadian-rhythm disruption. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2700. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-10563-9

- Slomski A. Circadian timing of medications affects CVD outcomes. JAMA. 2019;322(24):2375. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.20565

- Musiek ES, Bhimasani M, Zangrilli MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM, Ju YS. Circadian rest-activity pattern changes in aging and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(5):582-590. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4719

- Wilson JE, Blizzard L, Gall SL, et al. An eating pattern characterised by skipped or delayed breakfast is associated with mood disorders among an Australian adult cohort. Psychol Med. Published online October 16, 2019. doi:10.1017/S0033291719002800

- Jakubowicz D, Landau Z, Tsameret S, et al. Reduction in glycated hemoglobin and daily insulin dose alongside circadian clock upregulation in patients with type 2 diabetes consuming a three-meal diet: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(12):2171-2180. doi:10.2337/dc19-1142

- Ellingsen T, Bener A, Gehani AA. Study of shift work and risk of coronary events. J R Soc Promot Health. 2007;127(6):265-267. doi:10.1177/1466424007083702

- Sutton EF, Beyl R, Early KS, Cefalu WT, Ravussin E, Peterson CM. Early time-restricted feeding improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and oxidative stress even without weight loss in men with prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018;27(6):1212-1221.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.010

- Segal JP, Tresidder KA, Bhatt C, Gilron I, Ghasemlou N. Circadian control of pain and neuroinflammation. J Neurosci Res. 2018;96(6):1002-1020. doi:10.1002/jnr.24150< /a>

- Gabriel BM, Zierath JR. Circadian rhythms and exercise – re-setting the clock in metabolic disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(4):197-206. doi:10.1038/s41574-018-0150-x

- Thomas JM, Kern PA, Bush HM, et al. Circadian rhythm phase shifts caused by timed exercise vary with chronotype. JCI Insight. 2020;5(3):134270. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.134270

- Rodrigues NR, Macedo GE, Martins IK, et al. Short-term sleep deprivation with exposure to nocturnal light alters mitochondrial bioenergetics in Drosophila. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;120:395-406. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.04.549

- Murakami M, Tognini P. The circadian clock as an essential molecular link between host physiology and microorganisms. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;9:469. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2019.00469

- Swanson GR, Burgess HJ. Sleep and circadian hygiene and inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017;46(4):881-893. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2017.08.014

- Schmitt K, Grimm A, Dallmann R, et al. Circadian control of DRP1 activity regulates mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):657-666.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.01.011

- Mermet J, Yeung J, Hurni C, et al. Clock-dependent chromatin topology modulates circadian transcription and behavior. Genes Dev. 2018;32(5-6):347-358. doi:10.1101/gad.312397.118

- Garaulet M, Qian J, Florez JC, Arendt J, Saxena R, Scheer FAJL. Melatonin effects on glucose metabolism: time to unlock the controversy. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2020;31(3):192-204. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2019.11.011

- Mayo Clinic. Light therapy. Published February 8, 2017. Accessed March 23, 2020. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/light-therapy/about/pac-20384604